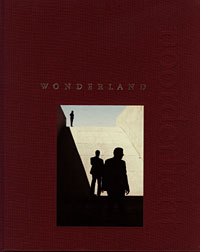

Wonderland

The premiere of The Geometry of Innocence was at the Noorderlicht Festival, Groiningen, The Netherlands in 1999 as part of the Wonderland exhibition. The catalog, pictured here, contained the work of 30 photographers. Cover image by Ken Schles.

Essays by Wim Melis, curator for Noorderlicht and Machiel Botman, guest curator.

List of participating photographers:

- Christer Strömholm

- Michael Ackerman

- Anton Corbijn

- Doug And Mike Starn

- Philip Gostelow

- Angela Trullinger

- Tom Fecht

- Jun Morinaga

- Morten Andersen

- Max Pam

- Antoine D'agata

- Laura Cohen

- Arno Nollen

- Roberto Mancuso Alvarez

- William Eggleston

- David Graham

- Ken Schles

- Lee Friedlander

- John Max

- Robert Mcfarlane

- Kiyoshi Suzuki

- Johan Van Der Keuken

- Philip-Lorca Dicorcia

- Tracey Moffatt

- Miguel Rio Branco

- Jlm Goldberg

- Adrienne Van Eekelen

- Tokio Ito

- Serge Clément

- Dave Heath

back to books

Wonderland by Wim Melis

Photographs

offer an illusion. They are the absolute ruler within their own rectangular

world. They may be a lie, but it is a lie rooted in the truth. Tangible surroundings

constitute the lifeblood of photography, the raw material, with which the

photographer spins his dreams, that justifies the photographic image. This

dramatic tension span between reality and fiction forms the heart of Wonderland.

A visual flood enters our safe living room daily via the media: the television

sends a million images into our home and a thousand advertising brochures fall

through the letter box. Man is flooded with images. Life presented by the media

seems to be a play performed for everyone's pleasure. Private lives are also

subject to continuous registration: a million snapshots are taken every day.

The functional power of the image as carrier of facts and means of seduction,

is undisputed in our visual economy. 'I'm in the picture, therefore I exist.'

The market of supply and demand has also been a great driving

force in culture, as the outside world often seems to have greater influence

than the photographer's personal drive. Artistic motivation is largely determined

by trends and movements. Photography, too, has long lost its innocence. Is there

still a place for images without a preconceived purpose or for stories with an

open ending? The photographers in Wonderland give a resolute affirmative answer.

The market's basal demands are of minor importance, the photographers are not

swayed by popular themes, accepted expectations or by the craze of the moment. The visual story

that these photographers employ is of a raw innocence. They are not looking for an aesthetic image, but are led by what offers itself to their camera. The photo is a reflection of a seemingly coincidental glance cast on a subject. It is an exploration of the world through the camera's eye. The photos therefore harbour a meaning that is hard to catch with words. The photographers in this book and accompanying exhibition present a kind of photography that places introspection above the analysis of the subject: the photographer's inner experience is at least as important as that what he sees and registers. The images provide an opening to another world and invite an exploration to a reality under the skin. The viewer enters the wonderland of the spirit through the window of the photograph. Wonderland provides the viewer with a range of intense impressions and experiences. In this photography, that what has been portrayed disappears into the background while free associations take upper

hand. The photo goes further than registering of time and space, it is not

only the carrier of information, but it suggests a story. A story that takes

place behind the surface of

the photograph and in the mind of the viewer

in an imaginary time and place. A dialogue is created between the image and

the viewer that stimulates the imagination. In Wonderland the photographers

retain their open view, untouched by the demands that the market tries to

make on them, and link it to the qualities of a universal, recognisable visual

language. This phenomenon transcends the artificial boundaries between genres

in photography. In this book, photographers from traditionally separate worlds

- the documentary and the conceptual- have been brought together. And still

their work easily flows over in one another, as becomes obvious when Doug

and Mike Starn's 'conceptual' images are placed next to Jun Morinaga's 'documentary'

images. The binding element between the photographers in Wonderland is their

fascination for life itself, with all its complex structures and human relationships.

The photos of Dave Heath and Philip-Lorca diCorcia are thirty years apart

and seem drastically different at first glance. At second glance, however,

the street photos from the sixties deal with the same forlornness as the

photos from the nineties. And how much do David Graham's extravagant Americans

really differ from Kiyoshi Suzuki's circus artists. The photographers in

Wonderland choose to create their own world. They are each working on a personal

document, like a writer of fiction, a poet of images. They are on a search

for the unattainable grip on reality. Another feature of these photographers

is 'nearness': they all choose nearby subjects, with which they are greatly

personally involved. The photos go there where life leads the photographer.

Sometimes the photographs are a reflection of private experiences, sometimes

the photographers are carried away

in the lives of other people or cultures. In both cases they try to deal

with that which presents itself to their lens without prejudice. Wonderland

starts in the fifties and ends in the nineties. The visitor will cross forty

years of visual tradition in this book. They will see images that transcend

the traditional boundaries between genres, between the documentary and the

conceptual. They will see raw images that lift the every-day out of oblivion

and make them visible in another way. What they will see in particular is

photographers who stay close to their hearts.

Wim Melis

Read below, "At Second Sight," by guest curator, Machiel Botman.